Author: Le Doanh, economist, former member of Vietnamese Prime Minister’s Advisory Council

Introduction: When the state becomes a “player” in the economy

In the 2015–2025 period, Vietnam witnessed the strong development of the technology, data and digital infrastructure sectors. Along with the wave of national digital transformation, many public agencies — including units under the Defense Ministry, the Ministry of Public Security, and other ministries — have established or joined enterprises operating in civil fields such as telecommunications, cybersecurity, data, electronic authentication, logistics, and innovation.

These models are not new in the world: many countries maintain public enterprises to carry out strategic tasks. However, in Vietnam, the participation of public sector units in the civil market has raised a big question: how to ensure that the boundary between “public service functions” and “business functions” is not blurred?

Context and trends in 2015–2025: from equitization to digital transformation

The past ten years is the period when Vietnam strongly promotes the reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and equitization, concretized through Resolution No. 12-NQ/TW (2017) on continuing to restructure, innovate and improve the efficiency of SOEs, clearly affirming: The State only holds capital in essential fields, security – defense, or natural monopolies. At the same time, in 2021, the Government issued Directive 855/CT-TTg (2021) requiring the review and reorganization of enterprises under the Ministry of Public Security, ensuring the separation between security tasks and commercial activities.

Meanwhile, the context of national digital transformation for the 2020–2025 period promotes the formation of public technology units, such as data centers, authentication platforms, innovation centers – both serving state tasks and having economic potential. It is at this intersection that legal, economic and competitive issues begin to arise.

Legal basis: when administrative power intersects with the market

According to the Vietnamese legal system, the basic principles to ensure transparency and equality between economic sectors are clearly stipulated in many documents including the 2013 Constitution, the 2018 Competition Law, the 2020 Enterprise Law, the 2018 Anti-Corruption Law, the 2014 Law on State Capital Management, as well as Decree 80/2020/ND-CP. However, implementing these regulations in practice is not easy, especially when an enterprise is both „security-serving“ and „economically autonomous.“

Structure and role of enterprises under the police forces

Since 2015, many enterprises belonging to or associated with public agencies have operated in the following fields:

Telecommunications & digital data – such as joint ventures and joint stock companies providing network infrastructure, digital identification solutions, information security.

Cybersecurity & Surveillance Technology – providing technical services, software, and data analysis solutions for government agencies and businesses.

Innovation and R&D Center – focusing on research and transfer of security technology, biometrics, and artificial intelligence.

These units have clear strengths: highly skilled human resources, privileged data, access to public projects and state infrastructure. However, these advantages also create an imbalance in competition with the private sector.

Institutional and economic conflicts arise: The problem of “double separation”: public service and business: Policemen or affiliated organizations, if they simultaneously run businesses, will face the risk of violating Article 20 of the 2018 Anti-Corruption Law. The difficulty lies in the fact that many businesses are of public origin, operating to serve security tasks, so they cannot fully apply the market mechanism. Specifically, the RAR Center (under Department of Administrative Police for Social Orders or C06 of the Ministry of Public Security) provides electronic authentication services / commercial services – has been certified by the Ministry of Public Security as qualified to provide electronic authentication services; there is a debate about the state-owned business unit conducting commercial services / collecting fees

Privilege and data advantages: Some units have access to citizen data, technical infrastructure or business information – factors that create advantages in technology bidding contracts. From a legal perspective, this requires a mechanism to control access and use of public data under the Personal Data Protection Law 2023 to avoid conflicts of interest. Specifically, the RAR Center (under C06) provides electronic authentication services / commercial services, GTEL/GMobile (the mobile network of the police) uses state infrastructure, giving priority to officers, whether it ensures transparency in corporate governance and fair competition in the market.

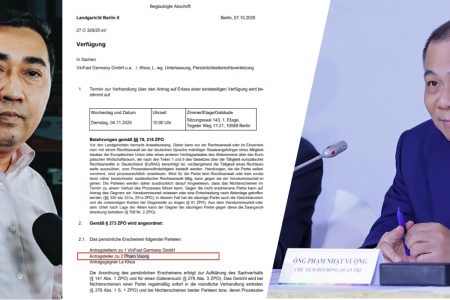

Lieutenant General Nguyen Minh Chinh, Director of the Department of Cyber Security and High-Tech Crime Prevention, has awarded 5 Hotline numbers to 5 units under the Ministry of Public Security.

Financial mechanism and transparency: Due to the security nature, most public enterprises do not publish their entire financial reports. However, Article 31 of the Enterprise Law 2020 requires all state-owned enterprises to publicize operational information, except for the part identified as state secrets. The question is: “Where is the boundary between ‘security secrets’ and ‘economic transparency responsibilities’?”

Competitive impact: When public enterprises participate in the telecommunications, data, or logistics markets, they can enjoy tax, land, or loan incentives and even be introduced to businesses by professional units to use their products and services. This seriously violates the principle of fair competition.

Macroeconomic perspective: impact on growth and the private sector

Research by the Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM, 2022) shows that the private enterprise sector contributes more than 42% of Vietnam’s GDP but is under great pressure from an unbalanced competition mechanism. Especially in the fields where the Ministry of Public Security has enterprises participating in business, this presence has two aspects: (1) Positive: contributing to shaping technical standards, ensuring system security and initial infrastructure investment. (2) Negative: can „crowd out“ private investment (crowding-out effect), when the market becomes dependent on a group of enterprises with administrative factors.

According to the World Bank (World Bank, 2023), if Vietnam increases the independence and transparency of SOEs, its GDP can increase by 2-3 percentage points per year thanks to the efficiency of resource allocation.

The Reverse Effect of Resolution 68 and Long-term Impact on Institutions and Innovation

Resolution 68/NQ-CP is considered an important milestone in Vietnam’s development thinking: promoting the private economic sector to become the driving force of the economy. However, while the policy aims to “open the way” for private enterprises, in reality, in some areas – especially technology, data and cybersecurity – we are witnessing a trend of “reverse presence” of the public sector in the civil market. The participation of enterprises belonging to the police or related to national security without a clear separation mechanism, can create an effect contrary to the spirit of Resolution 68: instead of encouraging, it makes the private sector afraid and narrows the competitive space.

When administrative power and economic power coexist in the same organization, the risk of “institutional bias” becomes obvious. Private enterprises, already disadvantaged in terms of capital and data, face competitors with privileged access to information, preferential treatment in land, credit, or approval processes. This situation not only distorts the market but also undermines the private sector’s confidence in the neutrality of the state. The long-term consequence is stagnation in innovation investment – as private enterprises are reluctant to enter “sensitive” areas, which are considered “gray areas” between the economy and security.

The institutional impact of this phenomenon is even deeper. The “hybridization” between public agencies and enterprises erodes the “one agency – one function” principle, making it difficult to reform public administration. The monitoring, auditing, and anti-corruption systems are hindered, because economic activities are shielded under the name of “security missions.” In the long term, this threatens the equitization process, slows down the restructuring of state-owned enterprises and reduces the national transparency index – which is a key criterion in international credit assessment and FDI attraction.

Regarding innovation, the private sector is often the place where new ideas and technologies arise thanks to a free competitive environment. However, when administrative power dominates both project allocation and technical standards, innovation is at risk of being “bureaucratized.” Public enterprises, despite their technical capacity, still find it difficult to maintain the spirit of autonomous innovation when all activities are bound by public procedures. Thus, the adverse effect of Resolution 68 is not only economic encroachment, but also ideological encroachment: instead of encouraging the creative market, institutions strengthen the ask-give mechanism, weakening the resilience of the digital economy.

Resolution 68 (on private economic development) recommends creating a level playing field, encouraging private enterprises, and limiting direct intervention by State agencies in competitive business activities. Units under the Ministry of Public Security directly participating in the market can create barriers to competition for private enterprises; create advantages based on power and violate the spirit of creating an environment for private sector development. The presence of public security enterprises in the economy can have a profound impact on the confidence of the private sector when small enterprises hesitate to invest in “near-security” sectors; reduce the motivation for reform when economic power is linked to administrative power, the equitization process is slowed down and the national transparency index is reduced.

International comparison: experience and institutional lessons

Many countries have faced the same problem as Vietnam: how to ensure national security without distorting the market. International experience shows that the problem is not whether to allow or not, but how to control and separate institutions.

In Korea, units under the Defense Ministry or the Ministry of the Interior are only allowed to participate in the economy through the PPP (Public–Private Partnership) model. All economic activities must be subject to independent audits and periodic reports to the National Assembly. Public enterprises participating in civil bidding are closely monitored, ensuring that they do not use data or administrative advantages for commercial advantage. This is a way to both protect national security and maintain a level playing field.

Singapore is a typical success story. Temasek Holdings Group – the state capital management agency – operates as a completely independent investment fund, separate from the administrative apparatus. Temasek does not represent any ministry or agency; all investment activities follow private enterprise standards, accountable to the market and the public. This clear separation helps Singapore both ensure control of state assets and avoid conflicts of interest.

In France and Germany, the enterprise model under the Ministry of Home Affairs is only allowed to produce and provide services directly serving public affairs (e.g., security equipment, internal information systems). All civil activities must be separated as legal entities and subject to commercial regulations like other private enterprises. This “institutional firewall” mechanism helps protect the principle that the state does not compete with citizens in the market space.

From the above experiences, Vietnam can draw two main lessons. First, it is necessary to establish a dual audit mechanism: a public monitoring channel for civil activities, and a secret channel serving national security. Second, it is necessary to build an independent state capital management model like Temasek, to ensure the separation between the administrative apparatus and economic investment activities. Otherwise, public power will easily “slip” into the market, leading to competition distortion and institutional efficiency decline.

Maintaining the boundary between power and the market

Maintaining the boundary between power and the market is not only a governance principle, but also a prerequisite for the sustainable development of the Vietnamese economy. Once public agencies act as both “referees” and “participants in the game” then trust in the market rules will be eroded. In a modern economy, institutional trust is the greatest social capital; without it, any reform will be difficult to sustain.

Legally, the Constitution and the Competition Law of Vietnam have clearly affirmed the principle of equality between economic sectors. However, the reality of implementation shows that the boundary between “public power” and “market activities” is being strongly challenged. Many businesses associated with public agencies can access infrastructure, data, and preferential policies that the private sector does not have. When privilege replaces competition, the market loses its function of allocating resources efficiently – and in the end, the state itself must bear the costs caused by such distortions.

Maintaining this boundary requires institutionalizing the “firewall” principle between public service and business: security and defense units should only participate in the economy through separate legal entities, with transparent governance mechanisms and independent civil liability. At the same time, it is necessary to strengthen the role of the State Audit, the National Competition Commission, and investigative journalism in monitoring the economic activities of public agencies.

But above all, maintaining boundaries is not just a matter of legal techniques, but a matter of institutional culture – that is, the state’s self-awareness in restraining its own power. When power is used within its limits, the market can play its role in allocating resources, and the state can maintain its prestige and legitimacy in the eyes of the public.

A healthy economy does not need the state to “do it for us” but needs the state to “create a framework.” Between power and the market, the boundary is not a wall, but a protective rope – so that both can operate in harmony, serving the public interest and the long-term development of the country.

The participation of public authorities in the economy is a natural part of the process of modern national development, but without a separate legal mechanism, it can distort the market, reduce productivity and stifle innovation.

From an institutional perspective, Vietnam’s biggest problem is not “whether” to allow state-owned enterprises to operate but “how” to ensure they operate transparently, efficiently, and do not overwhelm the private sector.

A strong economy requires not only security but also trust in the fairness and transparency of the market – where all entities, whether public or private, follow the same rules of the game.